Colliding Worlds of Dispute Resolution: Towards a Unified Field Theory of ADR

David A. Hoffman, 2010

David Hoffman surveys the field of alternate dispute resolution - from mediation to collaborative law. He compares them to the litigation model and analyzes their strengths and weaknesses. He discusses hybrid approaches to dispute resolution and reconciles the differences between the various approaches.

Financial Dispute Resolution in England

William Longrigg, 2010

This article sets out the way that the Financial Dispute Resolution Hearings work in England and Wales. These hearings provide compulsory non-binding evaluation by a judge in financial proceedings principally in the context of divorce at a relatively early stage of proceedings once the financial disclosure has been made. They have a high success rate in achieving settlement to avoid a full-blown contested hearing.

Alternative Resolution of Disputes in the Dominican Republic

Dilia Leticia Jorge Mera, 2010

In the presence of a judicial process that may be long, tedious and expensive, the concept of alternative dispute resolution is recently gaining popularity in the Dominican Republic, as it offers a rapid and effective means to settle legal disputes out of court. Presently, the Dominican Republic offers three mechanisms through which parties may attempt to settle their conflict outside of court: mediation, conciliation and arbitration.

The California Mediation Privilege

Suzanne Harris and David Marcus, 2010

By Suzanne Harris and David Marcus Meditation can be an effective and inexpensive method of settling divorce cases. Under California law all statements in the course of mediation are confidential which make setting aside an agreement reached during mediation difficult. The parties can agree in mediation to waive the “mediation privilege.” Nothing said or written during the mediation can be received in evidence, compelled in discovery, or compelled as testimony in any proceeding. If a party sends a document to the mediator and that document would have been discoverable in the absence of the mediation, the document remains discoverable. It is prudent be make it clear when the mediation begins and ends to ensure that only that which occurs during mediation is protected. Proving whether there was an agreement in mediation can be a challenge. Absent a written agreement, either audio or videotaping the agreement can be effective to show there was a waiver of the mediation privilege or an agreement regarding the substantive issues. The mediation privilege trumps the presumption of undue influence so it may be impossible to show that the agreement arrived in mediation was procured by undue influence. A client should be advised that because of the “super-privilege” afforded the mediation process, he or she will forfeit the ability to set the agreement aside. Despite these disadvantages, the benefits to mediation in most cases will outweigh the cost of litigation or attempting to settle a case without the assistance of a mediator.

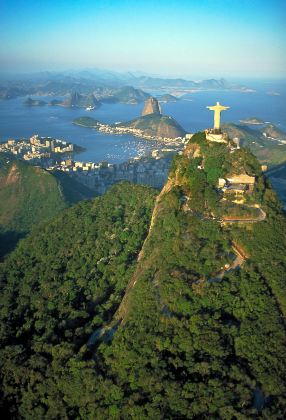

Alternative Resultion of Disputes in Family Law: The Brazil Perspective

Paulo Lins e Silva, 2010

Brazil has recently incorporated into its extra-judicial solutions the services of mediation, independent preliminary evaluation and a decision by a specialist, as alternatives to its slowed and burdened judicial system. Their incorporation to the Brazilian procedural system is noteworthy since it offers additional alternative means to resolve disputes between parties in an effective and less venomous environment where dialogue is favoured, as opposed to litigation, though extra-judicial agreements may only be sought when property is involved in disputes. The application of alternative dispute resolutions also relies on the consent of the parties to the conflict. Nevertheless, the judicial system is beginning to support and recommend extra-judicial solutions rather than litigation, something which was once considered as a threat to its constitutional mission to be sole arbiter to legal disputes. The promise of a less strained judiciary has been a strong proponent in convincing judges and officials to embrace a system that is less costly, which also favours a culture of dialogue rather than one of conflict. Even the legal profession must adapt to the inclusion of alternative dispute resolutions into Brazilian society. The role of lawyers must now be considered as first mediators, in the sense that they should be promoters of mutual agreements, especially in family law, when advising their clients whenever possible. Despite the fact that Brazil may easily incorporate these alternative means to agreements due to its current procedural system in place, more resources will need to be allocated to their development and promotion for their success.

The Private Judge: California Anomaly or Wave of the Future?

Jill S. Robbins, 2010

For the past 20 years, private judging has been largely a California phenomenon. Especially in the family law context (divorce, property division, custody, and support issues), it is a by-product of the myriad difficulties practitioners and litigants face in accessing an overwhelmed judicial system. Although private judging is the subject of some philosophical controversy, and use of a private judge to conduct evidentiary hearings and/or trial3 may not fit every family law case, it is an essential tool in the family lawyer’s arsenal. Clients should be counseled on whether the private judging option is in their interest. Private judges are typically experienced, knowledgeable retired judicial officers who are selected by counsel to hear and determine family law and/or civil matters and are compensated by one or both litigants. While there is no requirement that a private judge have prior experience as a judicial officer, most private judges are former bench officers, which enhance their credibility. The standards of proof are typically the same as in a public trial, and the outcome is enforceable in appellate courts. While the parties are free, by mutual agreement, to modify procedures and/or rules that would govern in a public courtroom, the Superior Court retains a supervisory role. Private judging is not a panacea. It is, however, a constructive and practical response to the fact that lack of resources renders our judicial system less responsive and more expensive than we would like it to be. This article addresses the pros and cons of private judging, including issues of confidentiality, security, flexibility, informality, and cost. It is an excellent primer for litigant considering opting out of the public court system and trying their matter before a private judge.

Are we counsel or Counsellors? Alternative Dispute Resolution & the Evolving Role of Family Law Lawyers in Canada

Esther Lenkinski and Maneesha Mehra, 2010

By Esther Lenkinski and Maneesha Mehra This article, written in Summer 2010, explores the increasing importance of ADR in Canada, the different ADR options available and how the role of family lawyers is evolving as a result. As would be expected, law and procedure varies between the different provinces. There are advantages and disadvantages of ADR. The advantages can include speed, control over the agenda, keeping financial information private and reduced cost. The disadvantages are the risk of dishonest or incomplete disclosure, lack of formal regulation and the fact that there are no real statistics or empirical studies as to the effectiveness of outcomes. Collaborative law is gaining ground in Canada. The process involves negotiations between the parties with their lawyers working with both of them and, where appropriate, other professionals to address the issues that the parties consider to be important. There is a disqualification clause requiring a change of lawyers if the process breaks down and litigation is to ensure. Cooperative law is a variation of collaborative which seeks to marry the traditional scope of family law practice with some of the fundamentals of collaborative. There is no disqualification clause. There are various models of mediation. Mediation can be with or without the parties’ lawyers being involved in the meetings. Techniques vary, but rights and interest-based mediation/negotiation are the most common, whereby what matters to the parties themselves drives the process. The parties can decide whether any factual information or evidence (including a failure to negotiate in good faith) disclosed in the mediation can be referred to in subsequent litigation (“open”) or remains privileged (“closed”). It is noted that in collaborative practice in Canada the whole process is closed. Another approach is for the mediator to be able to move on to act as an arbitrator in the event that the mediation is unsuccessful. Arbitration has remained a popular option, notwithstanding the fact that since the introduction of the Family Statute Law Amendment Act 2006 parties are prohibited from contracting out of appeals on questions of law, one of the consequences of which is the airing of the financial information that they might have wished to keep private. A real problem with ADR is that legislation has failed to keep pace with the development of ADR by failing to incorporate streamlined means of enforcing negotiated agreements through the court system. In effect, the defaulting party to an agreement can use the process of turning the agreement into an enforceable order as a back door means of challenging it without having to launch an official judicial review. This is seen as one of the fundamental flaws of the administration of ADR in Canada. In conclusion, the old adage that the fastest way to resolve a dispute is through the courts is being reassessed. The onus is on lawyers to consider all the options and to assist clients in making an informed decision about which approach is best suited to their needs. This raises issues about the training needed not only to help clients to choose the right dispute resolution path but also to identify, for example, mental health problems, ensuring that the vulnerable are effectively screened. ADR is an important part of the family lawyer’s toolbox, but there will always remain cases that are simply not suitable for ADR.

Culture in International Parental Kidnapping Mediations

Melissa A. Kucinski, 2010

In the handling of international parental kidnapping mediations, a mediator must be aware and understanding of both parent’s cultural customs and ways of communicating, since culture greatly influences how people interact with one another, and may reflect their way of thinking. Although a mediator cannot be trained to understand all cross-cultural ways, he can certainly be sensitive enough to recognise certain characteristic traits exhibited by the parties, and then attempt to decipher the parties’ intentions according to the context exhibited before him. In adopting such an approach, it may increase the effectiveness of his mediation session. In being attuned to the cross-cultural differences of the parties, a mediator may also be better positioned to assess the best interest of the child in question, particularly when the parents are from different cultural heritages, since culture will play an important role as to how the child will develop and grow. Thus, when a mediator is attentive to the cultural elements influencing the parties, he may have to vary his role and offer special accommodations, contrary to his traditional role of neutrality and impartiality. His familiarity to other cultures, and characteristic traits, may well be the key to having successful mediation sessions.

Alternate Dispute Resolution in Indian Family Law - Realities, Practicalities and Necessities

Anil Malhotra and Ranjit Malhotra, 2010

With a large and diverse society of close to 1.1 Billion people, the Indian legal system has a difficult task to offer an effective and swift judicial process with a rise in family law conflicts –divorces, custody, alimony, juvenile offenders and other matrimonial causes – despite the Family courts offering rapid settlements of disputes. With its judiciary clogged, India has adopted measures offering alternative dispute resolutions as an integral and imperative aspect of its judicial system to offer quick and effective means to resolve the increasing number of conflicts, whereby the judiciary would refuse to intervene until the legal issues are first referred to either arbitration, conciliation, mediation, judicial settlement or to Lok Adalat (a settlement court). Thus, before intervening and rendering judgment, the judiciary must discharge itself of the burden that the parties attempted an out-of-court settlement or reconciliation in some cases. Despite the current system in place, it may be improved by having citizens first turn to mediation or reconciliation of their own initiative, rather than invoke the courts. Also, the number of Family courts should be increased and become the final instance in family matters, due to their mission to offer speedy settlements and its proximity to the alternative dispute resolution process. Thus, putting matters to rest conclusively without further challenge, and in the process saving the superior courts’ time to deal with other matters. With the increase of matrimonial litigation, there has never been more need for further development of alternate dispute resolution than now, in India.